Nobility

Nobility is a social class that possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than most other classes in a society, and membership is usually hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages relative to non-nobles, or may be largely honorary (e.g. ‘order of precedence’) and vary from country to country and from era to era.

Historically, membership of the nobility in Ireland and the prerogatives thereof have been regulated or acknowledged by the Gaelic-Irish and Norse-Gaelic kings and chiefs, and later by the monarch or government of the British colonizers, thereby distinguishing the nobility from other sectors of the Irish upper-class.

Nonetheless, nobility per se has rarely constituted a closed caste; acquisition of sufficient power, wealth, military prowess or royal favour has often enabled commoners to ascend into the nobility. Some writers maintain this regular infusion of ‘new blood’ (from upwardly-mobile commoners) has maintained the vitality of the nobility in Ireland through its long and turbulent history.

Irish Nobility

The Irish Nobility refers to persons who fall into one or more of the following categories of nobility:

- The Gaelic nobility of Ireland who were or are descendants in the male line of at least one historical grade of king (Rí). This group includes the descendants of the Norse-Gaelic (Irish-Viking) kings as well.

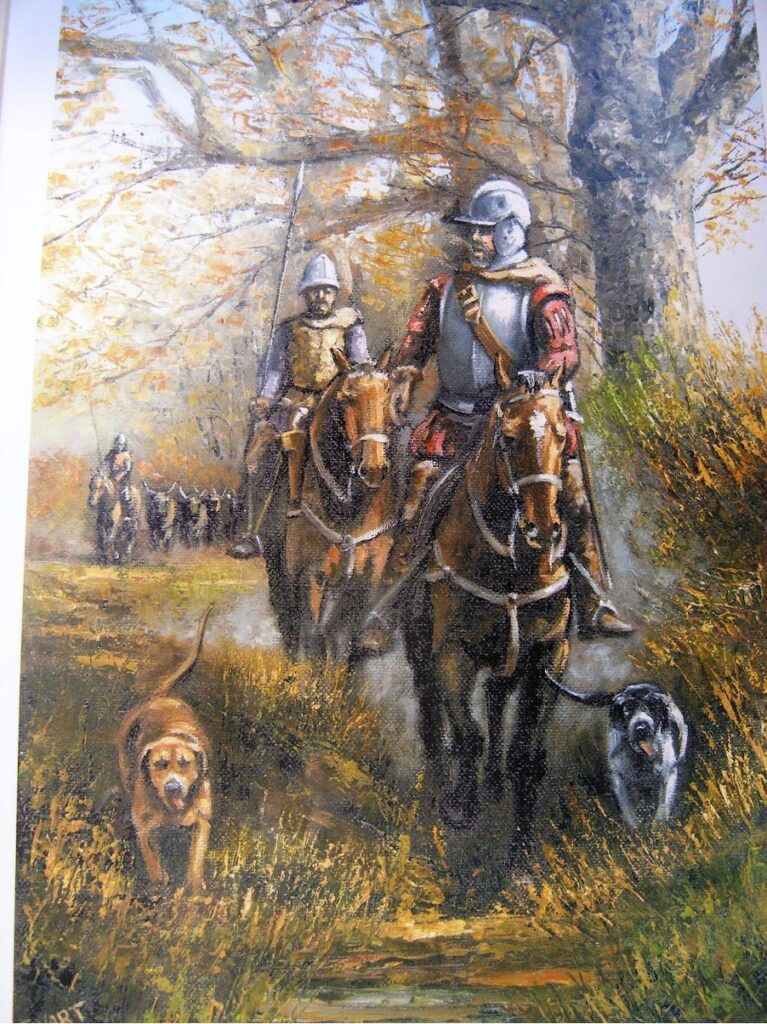

- The Hiberno-Norman or ‘Old English’ (Ireland) nobility who were the descendants of the settlers who came to Ireland from Wales, Normandy and England after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 – 1171 AD.

- The ‘Peerage of Ireland’ who owe their British titles to those created by the English, and later British, monarchs of Ireland in their capacity as Lord or King of Ireland.

These three groups are not mutually exclusive. There is a high degree of overlap between groups 1 and 2 (prior to the Treaty of Limerick in 1691). There is a lesser degree of overlap between groups 2 and 3 (prior to the declaration of the Republic of Ireland). There is also a lesser degree of overlap between groups 1 and 3. Such overlaps may be personal (e.g. a Gaelic noble who was ‘re-granted’ his titles by King Henry VIII of England), or they may be geographical (i.e. different noble traditions co-existing in neighbouring parts of the country, which were only distinguished by the date when they were finally conquered by the English administration in Dublin castle).

Clann territories were under the rule and control of a Chief, whom was elected by a vote of ancestral descendants (within three generations, a process called Tanistry) of the preceding Chief. The designation as Chief was also referred to as a King (Ri), Lord (Tiarna), or Captain of his countrie (or ‘captain of his nation’), all of which were roughly equivalent, prior to the collapse of the Gaelic order. The concept of a hereditary ‘title’ originated with the adoption of English law, the policy of surrender and re-grant and the collapse of the Gaelic order during the period from approximately 1585–1610. Because the election of a new chief would almost always be from the same family (or families) within a tribal area, each family developed a long history of ruling within an area, which gave rise to the concept of Gaelic nobility. However, ruling titles did not pass by hereditary descent; rather it was by election and bloodshed, given the absence of criminal penalties for the death of an opponent.

Subsequent to the end of the MacCarthy Mór sovereignty in the kingdom and territory of Desmond, descendants entitled to the highest Gaelic designation of ‘Chief of the Name’ of the MacCarthy Mór family, are also properly styled as Princes of Desmond. A secondary title of the MacCarthy Mór would derive from the lordship designation of his sept. For example, the current holder of the MacCarthy Mór ‘Chief of the Name’ title, Liam Trant McCarthy, is also titled as Lord of Kerslawny, by virtue of his position as senior-most in descent through the line of Sliocht Cormac of Dunguile (the Lordship of Kerslawny). Present day Gaelic nobles might be styled as either Flaith (prince), Ard Tiarna (high-lord), or Tiarna (lord).

The word Tiarna is from the old Irish-Gaelic word Tigerna, meaning ‘lord’ in the Gaelic world, approximately equal in rank to a ‘Baron’. An amusing example is James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven, a Norman-Irish nobleman of an ‘Old English’ (Catholic) family, called Tiarna Beag or ‘Little Lord’ because of his small height.

An Ard Tiarna is a ‘high lord’, approximately equal in rank to a ‘Count’ or an ‘Earl’, although many of such higher-rank still happen to prefer the Gaelic-title on its own.

These Gaelic-Irish titles no longer attach to any territories. They are honorifics, or, in legal parlance, ‘incorporeal hereditaments.’ Any lands which historically related to any given title, have long since become simply footnotes in the history of the title. In some cases, historically-provable Gaelic-Irish titles which resided (as ‘incorporeal hereditaments’) within the patrimony of Gaelic-Irish royal houses have been re-granted in modern times, in instances where the male line of the original title-holder(s) became extinct.

In later Gaelic sources, for example the Annals of the Four Masters, the term Ard Tiarna has also been frequently used to replace the title Rí (king) in cases where the authors or current tradition no longer regarded earlier regional and local dynasts as proper kings, even when they are styled such in contemporary sources.

In Gaelic-Ireland each person belonged to an agnatic kin-group known as a fine (plural: finte) or clann (plural: clanna). This was a large group of related people supposedly descended from one progenitor through male forebears. It was headed by a male chieftain, known in Old Irish as a cennfine or toísech (plural: toísig).

Although these groups were primarily based on blood-kinship, they also included those who were fostered into the group and those who were accepted into it for other reasons. (They would be better thought of as akin to the modern-day corporation.)

Succession to the chieftainship or kingship was through Tanistry. When a man became chieftain or king, a relative was elected to be his deputy or ‘tanist’ (Irish-Gaelic: tánaiste, plural tanaistí). When the chieftain or king died, his Tanist would automatically succeed him. The Tanist had to share the same great-grandfather as his predecessor and he was elected by freemen who also shared the same great-grandfather. This group of relatives was known as the Derbhfine.

Tanistry meant that the kingship usually went to whichever relative was deemed to be the most fitting and capable. Sometimes there would be more than one Tanist at a time and they would succeed each other in order of seniority. Some Anglo-Norman lordships in Ireland later adopted Tanistry from the Irish.

Gaelic-Ireland was divided into a hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs. The smallest territory was the túath (plural: túatha), which was typically the territory of a single kin-group. It was ruled by a rí túaithe (king of a túath) or toísech túaithe (leader of a túath). Several túatha formed a mór túath (over-kingdom), which was ruled by a rí mór túath or ruirí (over-king). Several mór túatha formed a cóiced (province), which was ruled by a rí cóicid or rí ruirech (provincial king). In the early Middle Ages the túatha was the main political unit, but over time they were subsumed into bigger conglomerate territories and became much less important politically.

Social Class

Gaelic-Irish society was structured hierarchically, with those further up the hierarchy generally having more privileges, wealth and power than those further down.

The top social layer was the sóernemed, which included kings, tanists, chieftains, highly skilled poets (fili), clerics, and their immediate families. The roles of a fili included reciting traditional lore, eulogising the king and satirising injustices within the kingdom. Before the Christianisation of Ireland, this group also included the druids (druí) and vates (fáith). The druids combined the roles of priest, judge, scholar, poet, physician, and religious teacher, while the vates were oracles.

Below that were the dóernemed, which included professionals such as jurists (brithem), physicians, skilled craftsmen, skilled musicians, scholars, and so on. A master in a particular profession was known as an ollam (modern spelling: ollamh). The various professions — including law, poetry, medicine, history and genealogy — were associated with particular families and the positions became hereditary. Since the poets, jurists and doctors depended on the patronage of the ruling families, the end of the Gaelic order brought their demise.

Below that were freemen who owned land and cattle (for example the bóaire).

Below that were freemen who did not own land or cattle, or who owned very little.

Below that were the unfree, which included serfs and slaves. Slaves were typically criminals (debt slaves) or prisoners of war. There is no evidence to suggest that slavery in Gaelic Ireland was anything more than a marginal phenomenon of luxury for the nobles.

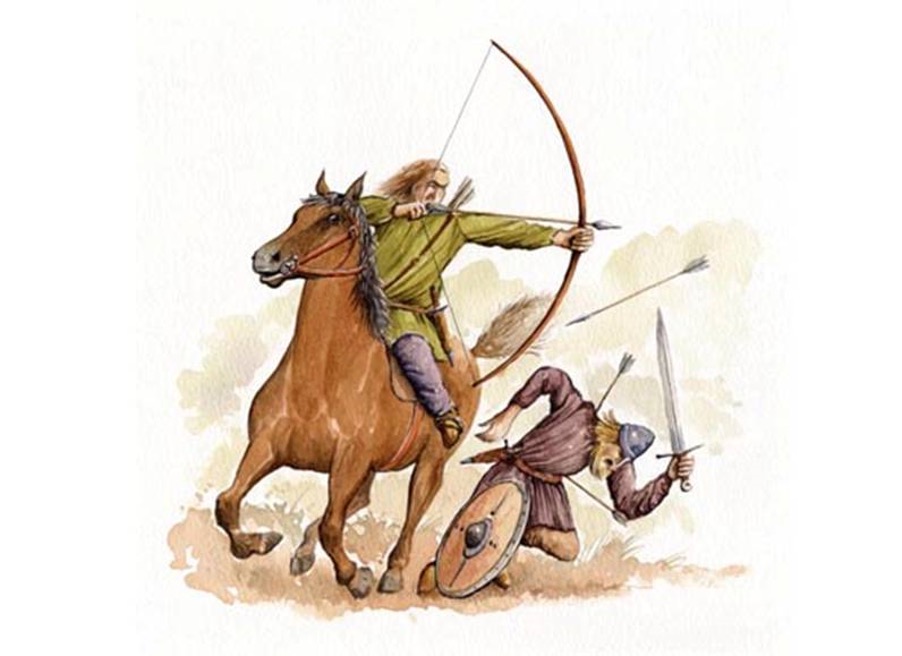

Warrior bands

The warrior bands (fianna) generally lived apart from society. A fian was typically composed of young men who had not yet come into their inheritance of land. A member of a fian was called a fénnid and the leader of a fian was a rígfénnid. Geoffrey Keating, in his 17th century History of Ireland, says that during the winter the fianna were quartered and fed by the nobility, during which time they would keep order on their behalf. But during the summer, from Bealtaine to Samhain, they were beholden to live by hunting for food and for hides to sell.

Class and social mobility

Although distinct, these social ranks were not utterly exclusive castes like those of India. It was possible to rise or sink from one social rank to another. Rising upward could be achieved a number of ways, such as by gaining wealth, by gaining skill in some department, by qualifying for a learned profession, by showing conspicuous valour, or by performing some service to the community. An example of the latter is a person choosing to become a briugu (hospitaller). A briugu had to have his house open to any guests, which included feeding no matter how big the group. For the briugu to fulfill these duties, he was allowed more land and privileges, but this could be lost if he ever refused guests.

A freeman could further himself by becoming the client of one or more lords. The lord made his client a grant of property (i.e. livestock or land) and, in return, the client owed his lord yearly payments of food and fixed amounts of work. The clientship agreement could last until the lord’s death. If the client died, his heirs would carry on the agreement.

This system of clientship enabled social mobility as a client could increase his wealth until he could afford clients of his own, thus becoming a lord. Clientship was also practised between nobles, which established hierarchies of homage and political support.

Historical influences on Gaelic-Irish society

Papal Bull

Ireland became Christianised between the 5th and 7th centuries. Pope Adrian IV, the only English (Anglo-Norman) pope, had already issued a ‘Papal Bull’ in 1155 AD giving the Anglo-Norman King Henry II of England authority to invade Ireland as a means of curbing Irish refusal to recognise Roman law (an as a means of eliminating the Irish Church, which was Orthodox, not ‘Roman’), and to collect a ‘papal tax’ from every household in Ireland (which is still collected by the Catholic Church to this day, and which is known as ‘Peter’s Pence’).

Importantly, for later English monarchs, the Papal Bull, Laudabiliter, maintained papal suzerainty over the island:

“There is indeed no doubt, as thy Highness doth also acknowledge, that Ireland and all other islands which Christ the Sun of Righteousness has illumined, and which have received the doctrines of the Christian faith, belong to the jurisdiction of St. Peter and of the holy Roman Church.”

King of Leinster

In 1166 AD, after losing the protection of High King Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, the King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was forcibly exiled by a confederation of Irish forces under the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Fleeing first to the English port-city of Bristol, and then to Normandy, Diarmait obtained permission from King Henry II of England to use his English subjects to regain his kingdom.

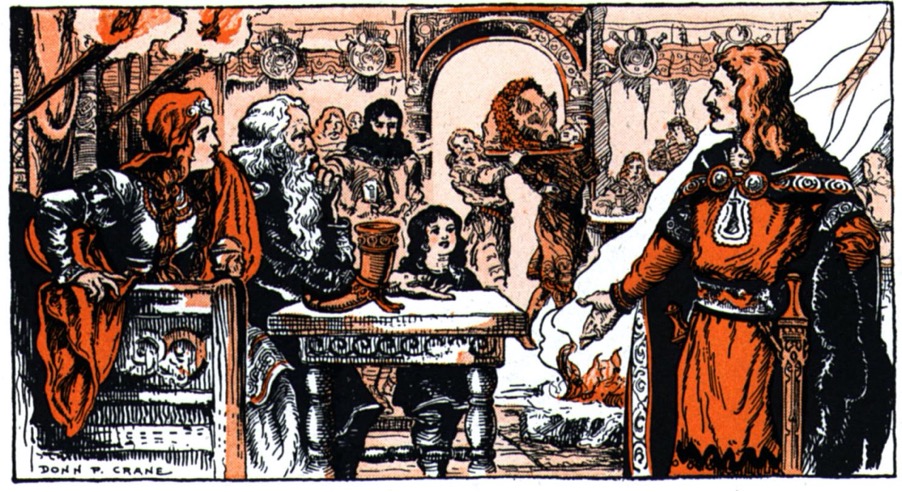

Richard de Clare (Stongbow)

By the following year he had obtained these services, and in 1169 AD the main body of Norman, Welsh, and Flemish forces landed in Ireland and quickly retook the Province of Leinster and the cities of Waterford and Dublin on behalf of Diarmait. The leader of the Norman force, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, more commonly known as ‘Strongbow’, married Diarmait’s daughter, Aoife, and was named Tánaiste to the Kingdom of Leinster. This caused consternation to Anglo-Norman King Henry II, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman Kingdom in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to visit Leinster to establish his authority.

The Marriage of Aoife and ‘Strongbow’

by Daniel Maclise (1854), a romanticised depiction of the union between Aoife and Richard de Clare in the ruins of Waterford.

The Anglo-Norman King Henry II of England landed in Ireland in 1171 AD, proclaiming Waterford and Dublin as Royal Cities. Pope Adrian’s successor, Pope Alexander III, ratified the grant of Ireland to King Henry in 1172 AD.

Treaty of Windsor

The 1175 AD Treaty of Windsor between the Anglo-Norman King Henry and Ruaidhrí maintained Ruaidhrí as High King of Ireland but codified King Henry’s control of Leinster, Meath and Waterford. However, with Diarmuid and ‘Strongbow’ dead, and with King Henry back in England, and Ruaidhrí unable to curb his vassals, the high kingship of Ireland rapidly lost control of the country. King Henry, in 1185 AD, awarded his younger son, John, the title Dominus Hiberniae, ‘Lord of Ireland’. This kept the newly created title and the Kingdom of England personally and legally separate. However, when Prince John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King of England in 1199 AD, the Lordship of Ireland fell back into personal union with the Kingdom of England.

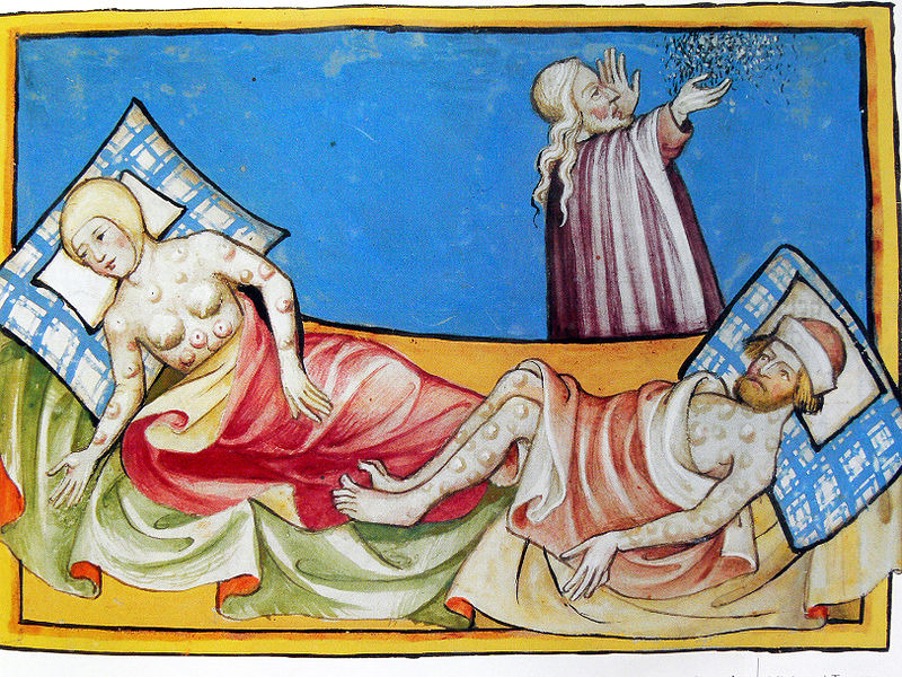

The Black Death

The Black Death broke out in Ireland in the Year 1348 AD. The annalists give fearful accounts of this ‘visitation’. Black Death appeared in Dublin first, and so fatal were its effects, that four thousand souls are said to have perished there from August to Christmas 1348 AD. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After the Black Death had passed, Gaelic-Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrank back to ‘the Pale’, a fortified area around Dublin. Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords intermarried with Hiberno-Gaelic noble families, adopted the Irish-Gaelic language and Irish customs and sided with the Gaelic-Irish in political and military conflicts against the English Lordship of Ireland. They became known as the ‘Old English’, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, were “more Irish than the Irish themselves.”

Statutes of Kilkenny

The authorities in the Pale worried about the Gaelicisation of Norman Ireland, and passed the ‘Statutes of Kilkenny’ in 1366 AD banning those of English-descent from speaking the Irish language, wearing Irish clothes or inter-marrying with the Irish.

However, the English government in Dublin had little real authority. By the end of the fifteenth century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared.

Hundred Years War

England’s attentions were diverted by the ‘Hundred Years’ War’ against the French (1337–1453) … and then by the ‘Wars of the Roses’, which were a series of dynastic wars (1450 – 1485 AD) for the throne of England (the ‘Wars of the Roses’ were fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet, being the houses of Lancaster and York). All around Ireland, local Gaelic-Irish and Gaelicised-Norman lords expanded their powers at the expense of the English government in Dublin.

Gaelic kingdoms and Gaelic-controlled lordships

Following the failed attempt by the Scottish Prince Edward Bruce (a Scottish-Norman) to drive the Irish-Normans out of Ireland, there emerged a number of important Gaelic kingdoms and Gaelic-controlled lordships.

Connacht

The Ó Conchobhair dynasty, despite their setback during the Bruce wars, had regrouped and ensured that the title King of Connacht was not yet an empty. Their stronghold was in their homeland of Sil Muirdeag, from where they dominated much of northern and north-eastern Connacht. However, after the death of Ruaidri mac Tairdelbach Ua Conchobairin 1384 AD, the dynasty split into two factions, Ó Conchobhair Don and Ó Conchobhair Ruadh.

By the late 15th century, internecine warfare between the two branches had weakened them to the point where they themselves became vassals of more powerful lords such as Ó Domhnaill of Tír Chonaill and the Hyberno-Norman Clan Burke of Clanricarde.

The Mac Diarmata Kings of Moylurg retained their status and kingdom during this era, up to the death of Tadhg Mac Diarmata in 1585 (last de facto King of Moylurg). Their cousins, the Mac Donnacha of Tír Ailella, found their fortunes bound to the Ó Conchobhair Ruadh.

The kingdom of Uí Maine had lost much of its southern and western lands to the Irish-Norman Clanricardes, but managed to flourish until repeated raids by Ó Domhnaill in the early 16th century weakened it.

Other territories such as Ó Flaithbeheraigh of Iar Connacht, ÓSeachnasaighof Aidhne, O’Dowd of Tireagh, O’Hara, Ó Gadhra, and Ó Maddan, either survived in isolation or were vassals for greater men.

Ulster

The Ulaid proper were in a sorry state all during this era, being squeezed between the emergent Ó Neill of Tír Eógain in the west, the MacDonnells, Clann Aodha Buidhe, and the Anglo-Normans from the east. Only Mag Aonghusa managed to retain a portion of their former kingdom with expansion into Iveagh.

The two great success stories of this era were Ó Domhnaill of Tír Chonaill and Ó Neill of Tír Eógain. Ó Domhnaill was able to dominate much of northern Connacht to the detriment of its native lords, both ‘Old English’ (Irish-Normans) and Gaelic-Irish, though it took time to suborn the likes of Ó Conchobhair Sligigh and Ó Ruairc of Iar Breifne.

Expansion southwards brought the hegemony of Tír Eógain, and by extension Ó Neill influence, well into the border lordships of Louth and Meath. Mag Uidir of Fear Manach would slightly later be able to build his lordship up to that of third most powerful in the province, at the expense of the Ó Ruaircs of Iar Breifne and the MacMahons of Airgíalla.

Leinster

Likewise, despite the adverse (and unforeseen) effects of Diarmait Mac Murchada’s efforts to regain his kingdom, the fact of the matter was that, of his twenty successors up to 1632 AD, most of them had regained much of the ground they had lost to the Normans, and exacted yearly tribute from the towns. His most dynamic successor was the celebrated Art mac Art MacMurrough-Kavanagh.

The Ó Broin and Ó Tuathail largely contented themselves with raids on Dublin (which, incredibly, continued into the 18th century). The Ó Mordha of Laois and Ó Conchobhair Falaighe of Offaly – the latter’s capital was Daingean – were two self-contained territories that had earned the right to be called kingdoms due to their near- invincibility against successive generations of Irish-Normans.

The great losers were the Ó Melaghlins of Meath: their kingdom collapsed despite attempts by Cormac mac Art O Melaghlain to restore it. The royal family was reduced to vassal status, confined to the east shores of the River Shannon. The kingdom was substantially incorporated into the Lordship of Meath which was granted to Hugh de Lacy (a Norman lord) in 1172 AD.

Munster

The Kingdom of Desmond (South Munster)

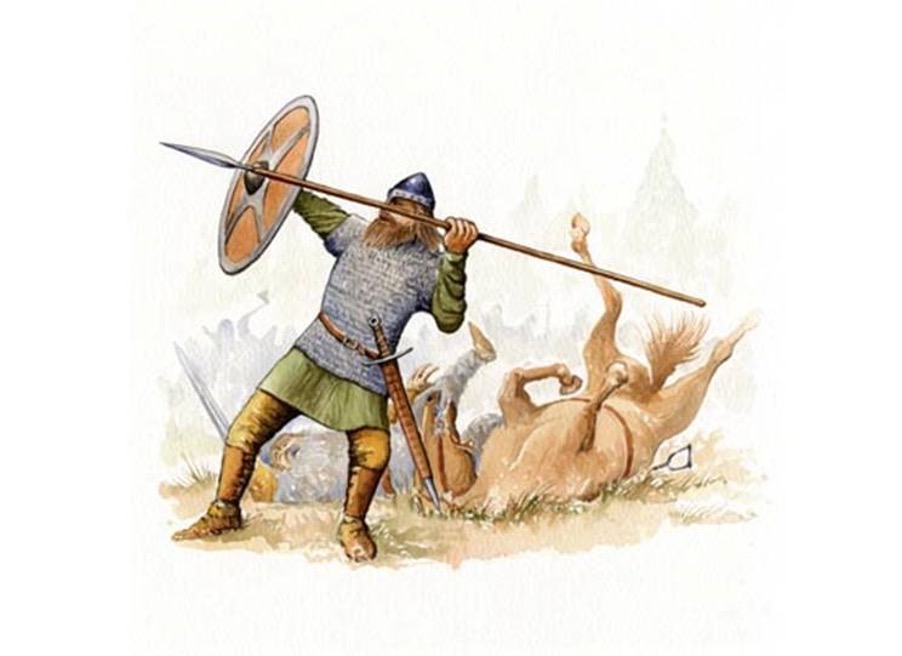

It was during this period that Finghin MacCarthy, King of Desmond, also known as Fineen of Ringrone (Fínghin Reanna Róin Mac Carthaigh), fought the Battle of Callann in August 1261, between the Anglo-Normans, under John FitzGerald, and the Gaelic-Irish forces of the MacCarthy Reagh dynasty of the Kingdom of Desmond.

The battle took place in the townland of Callan (or Collon) near modern day Kilgarvan, County Kerry. The Anglo-Norman defeat at Callan is traditionally viewed as marking the expulsion of the Anglo-Normans, mainly the ‘Geraldines (FitzGeralds), from the south and their confinement to north of the rivers Maine and Laune. North of the rivers suffered attack after attack from the MacCarthys for many years after Callan, but this is the region that would become Kerry. It was largely Finghin MacCarthaigh’s victory against the FitzGeralds that preserved Irish-Gaelic Desmond for the next three centuries.

The Kingdom of Thomond (North Munster)

Despite huge setbacks, the descendants of Brian Bóruma had, by surviving the Second Battle of Athenry and winning the decisive battles of Corcomroe and Dysert O’Dea, been able to suborn their vassals and eradicate the Normans from their home kingdom of Thomond. Their spheres of interest often met with conflict with Anglo-Normans such as the Earls of Desmond and Earls of Ormond, yet they ruled right up to the end of Gaelic-Ireland, and beyond, by expedient of joining the Protestant Church and becoming the O’Brien Earls of Thomond (a British title).

Tudor conquest of Ireland

From 1536 AD, King Henry VIII of England decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under English control. The Hiberno-Norman FitzGerald dynasty of Kildare, who had become the effective rulers of the Lordship of Ireland (‘The Pale’) in the 15th century, had become unreliable allies for the English king … so, King Henry VIII resolved to bring Ireland under English government control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions, or for foreign invasions of England. To involve the Gaelic-Irish nobility and to allow them to retain their lands under English law, the English policy of ‘surrender and re-grant’ was applied.

In 1541 AD, King Henry VIII upgraded Ireland from a ‘lordship’ to a ‘kingdom’, partly in response to his changing relationship with the papacy, which still had suzerainty over Ireland, following Henry’s break with the church.

Henry was proclaimed ‘King of Ireland’ at a meeting of the Irish Parliament that year. This was the first meeting of the Irish Parliament to be attended by the Gaelic-Irish princes as well as the Hiberno-Norman aristocracy.

With the technical institutions of government in place, the next step was to extend the control of the ‘Kingdom of Ireland’ over all of its claimed territory. This took nearly a century, with various English administrations in the process either negotiating or fighting with the independent Gaelic-Irish and ‘Old English’ (Norman-Irish) lords.

The conquest of Ireland was completed during the reigns of England’s Queen Elizabeth I and King James I, after numerous bloody conflicts.

England’s ‘Tudor conquest of Ireland’ (or re-conquest) took place under the Tudor dynasty of English Kings and Queens during the 16th century.

Following a failed rebellion against the English crown by ‘Silken Thomas’ FitzGerald, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, England’s King Henry VIII was declared King of Ireland by statute of the Parliament of Ireland, with the aim of restoring such central authority as had been lost throughout the country during the previous two centuries.

By conciliation and repression, the conquest continued for sixty years, until 1603, when the entire country came under the nominal control of King James I, exercised through his ‘privy council’ at Dublin. The English conquest of Ireland was complicated by the imposition of English law, language and culture, as well as by the extension of the Protestant ‘Church of England’ as the state religion of Ireland.

The Spanish Empire intervened several times at the height of the Anglo-Spanish War, and the Irish found themselves caught between their widespread acceptance of the Pope’s authority and the requirements of allegiance demanded of them by the English monarchy.

Destruction of the Old Gaelic Order

Upon completion of the ‘Tudor conquest of Ireland’, the polity of Gaelic-Ireland had been largely destroyed and the Spanish were no longer willing to intervene directly. This left the way clear for extensive confiscation of land in Ireland by English, Scots, and Welsh colonists.

The flight into exile in 1607 of Hugh O’Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone and Rory O’Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell following their defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601 and the suppression of their rebellion in Ulster in 1603 is seen as the watershed of Gaelic-Ireland. It marked the destruction of Ireland’s ancient Gaelic nobility following the English conquest, and it cleared the way for the ‘Plantation’ (colonization) of Ulster. After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the Gaelic-Irish lordships.

After the destruction of the Old Gaelic Order which followed the Battle of Kinsale, the Irish in the island of Ireland have had to contend with hundreds of years of English rule, with every Irish generation has been repeatedly subjected to an on-going system of ridicule, persecution, and discrimination.

All of the historic English discriminatory legislation and Penal Laws regarding Ireland have impacted all Irish people to some degree or other – such as England’s actions to eliminate Gaelic law and culture. Some particular actions by the British were also aimed at a particular segment or part of the Irish population.

One of those segments was small, and is actually now an extremely small percentage of the overall Irish nation (which is some 70 millions, worldwide). These are the people who descend from the formerly ruling Gaelic-Irish families, pre-Battle of Kinsale – who were the indigenous nobility of Gaelic-Ireland; many of whose ancestors were killed by the English, or forced to leave Ireland with the ‘Wild Geese’, destined for a difficult and dangerous life in Europe and the New World – and, today, their descendants take great pride in the accomplishments of their Irish ancestors, and they wish to maintain an awareness of what the ancient Irish cultural and governmental/organisational history really was.

Since 1921, the Irish Free State and the Republic of Ireland have ruled the people of Ireland as successor governments to England’s rule from Dublin Castle … these Irish successor governments, which are based on English Common Law and the Westminster parliamentary system (e.g. an unelected upper-house), continue to use British titles as a form of respect in Ireland, while the old Gaelic titles are never mentioned.

Centuries of false propaganda and centuries of servitude on many levels, until Irish Independence in 1921, resulted in a totally incorrect conception of the Old Gaelic Order of things, Chiefs-of-Name, etc. Much of this was the result of deliberate English policy and prejudice, starting with their Surrender and Re-grant policy of the mid 1500’s and culminating with the 1587 law under the first Queen Elizabeth I which ‘utterly abolished’ all Brehon law, Gaelic titles and successions, Irish cultural practices, language, religion, etc. When, in fact, our Irish culture and governmental genius was far older and more advanced than theirs, only it was different … which the English refused to accept and thus decided to eliminate. Forever.

And, the English laws to ‘utterly abolish’ all aspects of the heritage and culture of the Irish were added to, again and again, during the following centuries by specific local actions and other legislation. The objective of the English was to completely eliminate the centuries-old Gaelic culture, referring to the nobility of Gaelic-Ireland as no more than ‘Chiefs of Savage Clans’ …

However, these ancient rights of the nobility of Ireland were never relinquished in international law, irrespective of the illegal suppression of our whole history by an invader, by force.

These Gaelic-Irish titles no longer attach to any territories. They are honorifics, or, in legal parlance, ‘incorporeal hereditaments.*’ Any lands which historically related to any given title, have long since become simply footnotes in the history of the title.

* In law, a hereditament (from Latin hereditare, to inherit, from heres, heir) is any kind of property that can be inherited. Hereditaments are divided into corporeal and incorporeal. Corporeal hereditaments are “such as affect the senses, and may be seen and handled by the body; incorporeal are not the subject of sensation, can neither be seen nor handled, are creatures of the mind, and exist only in contemplation”. An example of a corporeal hereditament is land held in freehold. Examples of incorporeal hereditaments are hereditary titles of honour or dignity, heritable titles of office, coats of arms, prescriptive barony, rights of way, etc.

British titles have nothing to do with the former Kingdom of Desmond and have no relationship in terms of any Gaelic Irish titles anywhere in Ireland. They have nothing to do with the history or grants or definitions used by the Gaelic-Irish nobility when the Old Gaelic Order was operative in Ireland, or now.

Gaelic-Irish titles were – and are – the property of the various Irish royal houses and their subordinates per documentation, historical usage and ‘chief rents’ paid, etc.

Gaelic-Irish titles and usages/ inheritances have no legal relationship to any laws ever passed by any British government, or by any government in Ireland still ruled by a British government in one of its personalities. Those governments had no right to outlaw Gaelic-Irish titles/ practices, or legislate about Irish structures, however much those governments tried to abolish by force and duress the Old Gaelic Order, including Gaelic-Irish titles. Thus English-inspired laws abolishing Gaelic-Irish titles (or abolishing ‘feudalism’ 1660 – 1662) or any other law on any subject passed when England/ Great Britain/ UK were controlling Ireland have nothing to do with the Old Gaelic Order, and are rejected as irrelevant.

Those Irish structures and the Brehon Law relating to them are not subject to any laws passed relating to them by any current Irish government, as that government is a ‘successor state’ and operates under the historic English common law which it accepted in lieu of historic Irish law. In effect, the Irish government of today has nothing legally to say either about historic Gaelic titles or about British titles emanating from the ‘previous’ de facto British government in Ireland.

(Nonetheless, there are people in Ireland – and in what was the Kingdom of Desmond – who still legally bear titles emanating from a British government prior to Irish Independence in 1922. And they and many of their ancestors have proved their total commitment to Irish nationalism and freedom. Many are ‘Irish’ in every manner including their birth and passports, and are publicly devoted to the idea of an Irish nation – which encompasses people of all backgrounds as citizens.)

It is important that the history and heritage of the Irish-titles of Old Gaelic Order lives on. And, it is important that there are suitable cultural custodians for this aspect of the Old Gaelic Order, who will ensure these icons of our Gaelic history and heritage survive, and that they are passed on to future generations of Irishmen.

The Kingdom of Desmond Association, is only one of many recent initiatives among individuals, groups, academics, etc. to ‘recapture’ the total treasure of Irish history pre-Kinsale. Which we ourselves have neglected since 1921 as is evident from simply looking at our own textbooks in Irish schools, which teach our own children very little about the Gaelic order of things, seemingly preferring to imply that Gaelic Ireland was a ‘republican’ world – which it never was, of course.

It is not difficult to understand that, after 1921, the British Empire’s ‘successor’ Irish Free State and the ‘successor’ Republic of Ireland *, who succeeded the English at Dublin Castle (with the ‘Irish State’ simply substituted for the ‘English Crown’), would be opposed to the concept of an English-style of aristocracy in Ireland. But for these Irish ‘successor’ governments to turn their backs on the existence of the native Irish nobility of the Old Gaelic Order, was to ‘throw the baby out with the bath water.”

* The Irish Free State and the Republic of Ireland are ‘successor governments’ to the British Empire : as part of Irish ‘independence’, Ireland adopted English Common Law; and ‘Crown Land’ became ‘State Land’, etc …

And, when a Brit’ titleholder comes to Ireland, his Brit’ title is used fawningly by people in the Irish government, whenever he is addressed.

It would be a step in the right direction if Irish Republic ‘successor’ governments would use the old Gaelic titles as a form of respect in Ireland, in the same way they continue to use British titles as a form of respect in Ireland.